Frank J. Dainello and Marco A. Palma

Historically, Texas ranked third in vegetable production behind California and Florida. Over the past five years, however, vegetable acreage has steadily declined to the point where Texas now ranks sixth. The acreage decline is attributed to serious problems with insects, diseases, and drought conditions during this period in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the state’s major vegetable production region. Also during this period of time the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was implemented, as well as other international trade agreements. As a result, a significant number of vegetable acreage have slid south across the border. Competition from Mexico is causing a closing of market windows previously dominated by Texas.

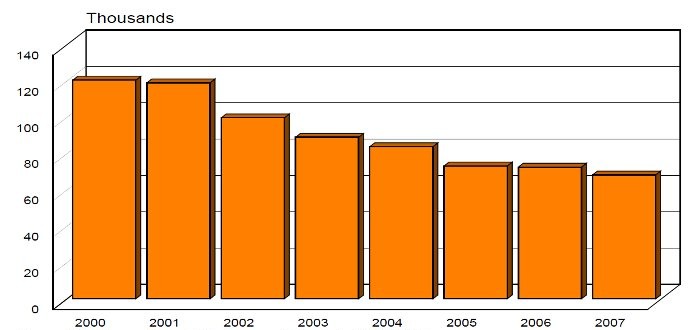

Figure I-1 shows the vegetable acreage in Texas for the past five years. Other states producing vegetables in large quantities include Georgia, Arizona, New York, Michigan, North Carolina, and Washington.

Figure I-1. Texas Vegetable Acreage Planted: 2000-2007

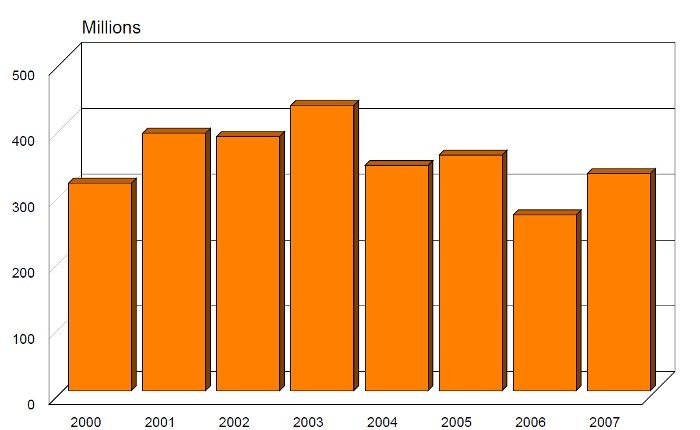

The Texas vegetable industry has an annual, on-farm value averaging approximately $350,000,000 (Figure I-2.) Texas vegetable crop values over the past eight years have ranged from a high of $433,136,000 in 2003 to a low of $314,922,000 in 2000.

Figure I-2. Texas Vegetable Crop Value: 2000-2007

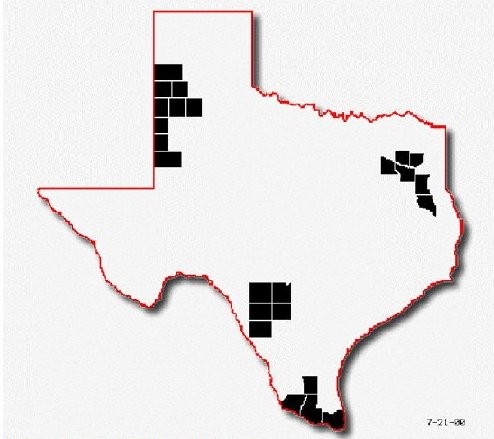

Vegetable production is scattered across the state. However, the four major vegetable producing regions of Texas are the Rio Grande Valley, the San Antonio or Winter Garden, the High Plains, and East Texas (Figure I-3.) Other producing areas within the state include the Trans-Pecos, the Coastal Bend, the North Texas area along the Red River, and the Laredo-Eagle Pass area. The leading vegetable producing counties in the state are: Hidalgo, Starr, Cameron, Deaf Smith, Frio, Uvalde, Zavala, Webb, Hale, Castro, Lamb, and Duval.

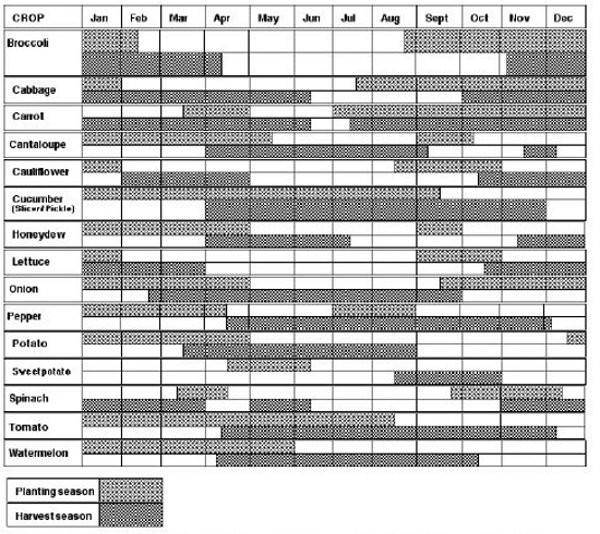

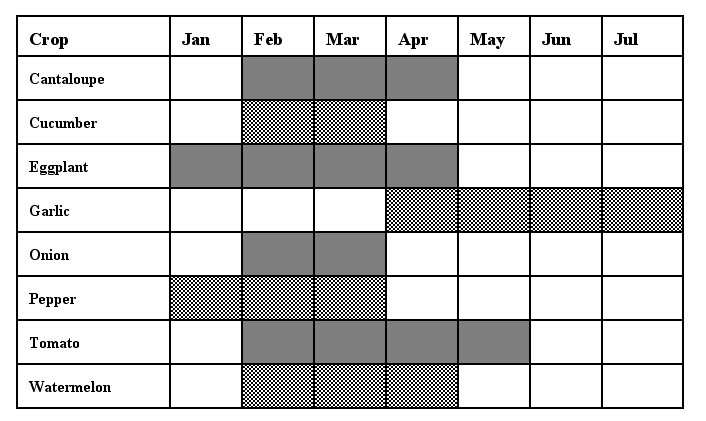

The majority of the vegetable crops are produced for the wholesale market on relatively large acreage farms, 500+ acres. Figure I-4 indicates the usual planting and harvesting dates for the state’s major vegetable crops. The crops are harvested, primarily by hand, and hauled to a packing shed where they are cleaned, graded, packed, and prepared for shipment to markets within and outside the state. Some vegetables, such as cabbage and spinach, are often field packed, eliminating the need for a packing shed. A few crops such as carrots, sweet potatoes, green beans, potatoes and most of the processing crops such as carrot, pickling cucumber, greens, and spinach are mechanically harvested.

Figure I-3. Major Vegetable Production Regions

Figure I-4. Usual planting and harvest seasons for selected Texas Vegetables.

Texas vegetables reach consumers nationwide primarily through truck shipment to large chain stores and supermarkets. As indicated in Figure I-4, Texas vegetable production is a year round business. This is one of the benefits that the state has over most others in the US. Figure I-5 shows the seasonal availability of selected vegetables imported from Mexico, which compete with Texas for markets during the late winter and early spring months. The major vegetables imported into the United States from Mexico include tomatoes, cantaloupes, broccoli, cucumbers and onions.

Figure I-5 Availability of Selected Vegetable Imports from Mexico

A major portion of the state’s vegetable crop is handled and marketed by brokers, shippers, and/or grower-shippers. Brokers are usually only involved in selling the produce, charging the grower a percent of the sale price for locating a market for the vegetables. Shippers usually operate packing or grading sheds and charge the grower for many of the associated marketing and handling costs such as harvesting, hauling, grading, packing, and selling. These expenditures are usually deducted from the wholesale price obtained for the vegetables by the shipper. The grower is then paid the remaining balance to cover production costs and profit. Grower-shippers function much the same as shippers, but normally grow and market their own vegetables as well as those of other growers.

Interest in vegetable production has increased in recent years among small-acreage producers located near high population areas. Consequently, there is renewed interest among some producers in marketing direct to the consumer through pick-your-own operations, roadside stands, roadside markets, community supported agriculture (CSA) and farmer’s markets. Much of this interest is the result of the consumer’s desire to obtain locally grown “farm fresh” produce. Approximately 5 percent of vegetables grown each year in Texas are sold directly to the consumer through these direct market outlets.