This section of the handbook outlines the general characteristics of the potential market outlets described in the previous section. These characteristics include trends in priced received for organic produce and general merchandising considerations such as quality and appearance, packaging, proper identification, signage and promotional materials, and display techniques. These topics are discussed below.

Trends in Prices

Many fruit and vegetable producers are attracted to organic production techniques because of the potential price premiums they may receive for organic produce as compared to conventional produce. Such premiums are only possible because some consumers are willing to pay higher prices for organic produce at the retail level. Recent surveys (1) indicate that consumers are willing to pay an average premium of 20 to 30 percent above conventional produce prices, depending upon the commodity. Any additional margins at the retail level are met with resistance from customers. Thus, prices paid to farmers will be at the same level of premium.

A question that many organic retailers are often asked is, “Why is the price of organic produce higher than that of conventional produce.” There are several reasons for higher organic prices including (2):

- Yields of organic crops maybe lower due to increased cosmetic damage and greater losses to insects, fungi and bacteria. Thus, costs of production must be spread over fewer units.

- Many organic crops require higher labor costs for more intensive fertilization and weed, insect and disease control programs.

- Wider plant spacings used in organic production allow air and sunlight to reduce disease, but also reduce total plants and yields per acre.

- Low supply and increasing demand allow growers to ask and receive higher prices for their organic crops.

In light of these factors, it is obvious that retail prices are not only reflective of the forces of supply and demand but of the additional costs that growers themselves may face. Thus, growers need to carefully examine the costs of production for organic fruits and vegetables on a per crop basis. Unfortunately, at the time of this writing, enterprise budgets for organic fruits and vegetables are not available. However, Appendix A at the end of this section discusses enterprise budgets and their uses. Using this format, growers may develop budgets that reflect their own cost structures. Growers may find that after budgets are developed for the proposed organic enterprises, the cost of organic inputs combined with additional labor requirements may exceed any premiums associated with organic produce.

At this time, the Federal Market News Service does not provide any price information regarding organic fruits and vegetables. However, in 1984, the Organic Market News and Information Service (OMNIS) was established by a joint effort of the Committee for Sustainable Agriculture and the California Certified Organic Farmers. The purpose of OMNIS is to provide weekly volume and grower and wholesale prices for more than 100 organically grown commodities.

However, the OMNIS reports are not without flaw. Changes in personnel, data collection periods, numbers of wholesalers reporting and geographic distribution of reporting wholesalers has at times affected the accuracy of OMNIS reports. However, at this time, OMNIS is the only systematic effort to provide market information on organically grown produce.

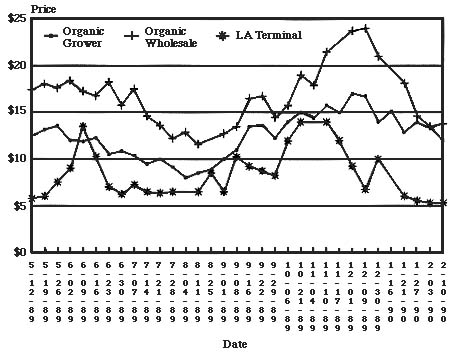

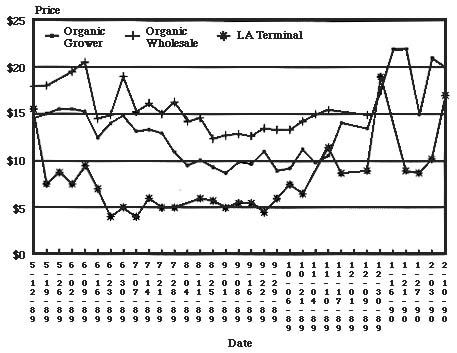

As an example of conventional versus organic prices reported by OMNIS, Tables 1 and 2 present price information for green romaine lettuce and red cherry tomatoes, respectively (3). For each week (mid-May 1989 to mid-February 1990) the volume shipped, organic grower price, organic wholesale price, Los Angeles terminal market wholesale price for non-organic produce and the average premium of organic over terminal market price are presented. These data are presented graphically in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1. OMNIS price and volume data for organically grown lettuce.

| Date | Volume (cartons) | Avg. price organic grower | Avg. price organic wholesale | Avg. wholesale price LA terminal mkt. |

Organic premium (percent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5/12/89 | 113 | 12.50 | 17.40 | 5.75 | 203 |

| 5/19 | 423 | 13.15 | 18.00 | 6.00 | 200 |

| 5/26 | 222 | 13.55 | 17.60 | 7.50 | 135 |

| 6/2 | 110 | 12.00 | 18.38 | 9.00 | 104 |

| 6/9 | 115 | ll.88 | 17.25 | 13.50 | 28 |

| 6/16 | 94 | 12.25 | 16.75 | 10.25 | 63 |

| 6/23 | 31 | 10.50 | 18.25 | 7.00 | 161 |

| 6/30 | 51 | 10.88 | 15.75 | 6.25 | 152 |

| 7/7 | 112 | 10.38 | 17.50 | 7.25 | 141 |

| 7/14 | 68 | 9.50 | 14.63 | 6.50 | 125 |

| 7/21 | 103 | 10.00 | 13.67 | 6.38 | 114 |

| 7/28 | 211 | 9.15 | 12.24 | 6.50 | 88 |

| 8/4 | 108 | 8.03 | 12.88 | — | — |

| 8/11 | 20 | 8.50 | 11.63 | 6.50 | 79 |

| 8/25 | 65 | 8.86 | — | 8.50 | — |

| 9/1 | 66 | 10.00 | 12.75 | 6.50 | 96 |

| 9/8 | 20 | 11.00 | 13.50 | 10.25 | 32 |

| 9/16 | 50 | 13.50 | 16.50 | 9.25 | 78 |

| 9/22 | 14 | 13.63 | 16.75 | 8.75 | 91 |

| 9/29 | 45 | 12.29 | 14.50 | 8.25 | 76 |

| 10/6 | 109 | 14.00 | 15.75 | 12.00 | 31 |

| 10/21 | 33 | 15.00 | 19.00 | 14.00 | 36 |

| 11/4 | 85 | 14.40 | 17.90 | — | — |

| 11/10 | 73 | 15.75 | 21.50 | 14.00 | 54 |

| 11/17 | 113 | 15.00 | — | 12.00 | — |

| 12/1 | 85 | 17.00 | 23.75 | 9.25 | 157 |

| 12/9 | 51 | 16.75 | 24.00 | 6.75 | 256 |

| 12/30 | 101 | 14.00 | 21.00 | 10.00 | 110 |

| 1/16/90 | 98 | 15.13 | — | — | — |

| 1/21 | 146 | 12.88 | 18.10 | 6.00 | 202 |

| 1/27 | 62 | 13.95 | 14.60 | 5.50 | 165 |

| 2/3 | 58 | 13.38 | 13.50 | 5.25 | 157 |

| 2/10 | 106 | 12.00 | 13.75 | 5.25 | 162 |

| — Not available. | |||||

| Source: Organic Wholesale Market Report.” OMNIS, Colfax, CA. | |||||

Table 2. OMNIS price and volume data for organically grown cherry tomatoes.

| Date | Volume (flats) | Avg. price organic grower | Avg. price organic wholesale | Avg. wholesale price LA terminal mkt. |

Organic premium (percent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5/12/89 | 20 | 14.50 | 17.90 | 15.50 | 15 |

| 5/19 | 64 | 15.00 | 18.00 | 7.50 | 140 |

| 5/26 | 129 | 15.50 | — | 8.75 | — |

| 6/2 | 85 | 15.50 | 19.50 | 7.50 | 160 |

| 6/9 | 20 | 15.25 | 20.50 | 9.50 | 116 |

| 6/16 | 120 | 12.45 | 14.50 | 7.00 | 107 |

| 6/23 | 35 | 14.00 | 14.88 | 4.00 | 272 |

| 6/30 | 24 | 14.00 | 19.00 | 5.00 | 280 |

| 7/7 | 126 | 13.21 | 15.22 | 4.00 | 281 |

| 7/14 | 196 | 13.36 | 16.16 | 6.00 | 169 |

| 7/21 | 133 | 13.00 | 15.00 | 5.00 | 200 |

| 7/28 | 82 | 11.00 | 16.28 | 5.00 | 226 |

| 8/4 | 218 | 9.56 | 14.25 | — | — |

| 8/11 | 261 | 10.12 | 14.62 | 6.00 | 144 |

| 8/25 | 173 | 9.40 | 12.43 | 5.75 | 116 |

| 9/1 | 100 | 8.74 | 12.78 | 5.00 | 156 |

| 9/8 | 92 | 9.94 | 12.90 | 5.50 | 134 |

| 9/16 | 127 | 9.71 | 12.70 | 5.50 | 131 |

| 9/22 | 263 | 11.08 | 13.52 | 4.50 | 200 |

| 9/29 | 84 | 9.00 | 13.37 | 6.00 | 123 |

| 10/6 | 108 | 9.25 | 13.37 | 7.50 | 78 |

| 10/21 | 50 | 11.31 | 14.27 | 6.50 | 120 |

| 11/4 | 62 | 9.88 | 15.00 | — | — |

| 11/10 | 29 | 10.65 | 15.46 | 11.50 | 34 |

| 11/17 | 59 | 14.09 | — | 8.75 | — |

| 12/1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 12/9 | 65 | 13.51 | 14.94 | 9.00 | 66 |

| 12/30 | 25 | 17.25 | — | 19.00 | — |

| 1/16/90 | 16 | 22.00 | — | — | — |

| 1/21 | 14 | 22.00 | — | 9.00 | — |

| 1/27 | 8 | 15.00 | — | 8.75 | — |

| 2/3 | 10 | 21.00 | — | 10.25 | — |

| 2/10 | 2 | 20.00 | — | 17.00 | — |

| — Not available. | |||||

| Source: Organic Wholesale Market Report.” OMNIS, Colfax, CA. | |||||

An analysis of these data shows that in some weeks organic produce commands large price premiums over conventional produce. For example, between May 1989 and February 1990, the wholesale price premium for organic romaine lettuce ranged from 28 percent to 256 percent. The price premium for red cherry tomatoes ranged from 15 percent to 281 percent during the same time period.

Figure 1. Organic grower price, organic wholesale price, and LA terminal market price reported by OMNIS for organically grown lettuce

Previous studies of data collected by OMNIS have shown that organically grown produce prices do not always move in concert with those of conventional produce (4). However, discussions with Texas wholesale distributors indicated that conventional prices provide a benchmark in determining prices paid to growers. Thus, the same market forces affecting prices of conventional produce will affect prices received for organic produce. In particular, surpluses and shortages have been reported in relatively close proximity, indicating much more localized markets than for conventional produce. Thus, even though the market for organic produce may be far from saturated, there may be times when the grower faces a market surplus for the organic crop being marketed. In such situations, wholesale buyers may go ahead and purchase the organic commodity, but the price paid to the grower will be the same as or close to the conventional produce price.

Figure 2. Organic grower price, organic wholesale price, and LA terminal market price reported by OMNIS for organically grown cherry tomatoes

Crops With Most Potential

One of the most common questions potential growers of organic produce ask is, ‘What crops should I grow?” Unfortunately the answer is not clear cut. In general, most organic buyers in Texas have indicated that if a conventional produce item does well then its organic counterpart has potential to do well. Also, crops which typically have few insect and disease problems are perhaps the easiest crops to produce organically. Carrots, potatoes, onions, broccoli, cauliflower and leafy greens have been mentioned as potential organic candidates. There are many others, but the resources that Texas organic producers have available to them across the state vary considerably because of differences in soil, rainfall, fertility and other production factors. Growers should contact their local county extension agent or area Extension horticulturist for information on crops that maybe suitable for a particular region of the state.

Because organic crops having the most potential will be closely related to their conventional counterparts, growers should carefully study trends which have affected conventional produce prices and volume. Market window analyses may be helpful in determining when to market crops for maximum returns. Appendix B provides a simplified overview of the use of market window analyses. Growers can use these to determine the best planting dates, varieties (early or late maturing) and marketing opportunities.

Merchandising

The way organic produce is merchandised is important In general, the merchandising of organic produce is similar to that of conventional produce. However, special activities may be necessary for proper identification and for maintaining shelf life.

As far as quality is concerned, organic produce must meet or exceed acceptable cosmetic standards. That is, the appearance of organic produce must be as good as conventional produce. Wholesale distributors and retailers in Texas indicate that there are no separate grades or standards for organic produce, and that all produce (organic or conventional) must at least meet USDA Grade 1 standards.

To maintain post-harvest quality, growers should cool (if cooling facilities are available), pack and deliver (depending on buyer) the produce as quickly as possible. The produce must be cleaned, graded and securely packed prior to delivery. Standard packing boxes for conventional produce may also be used for packing organic produce. However, the packages should be clearly identified as organic. In some markets, smaller-than-standard containers may be required, but this can be worked out with the buyer.

One problem that retailers have had in handling organic items in the produce department is how to distinguish organic produce from conventional produce. If prices are different, there could be a loss of profits if organic produce is not clearly identified at checkout. Growers and packers may solve this problem by using special bands, tapes, tags, labels, labeled consumer packs, etc. to identify the product as organic. Growers with TDA certification may have access to appropriate tags and logos. Growers often receive a premium for making the effort to use these identification procedures. This may be negotiated with potential buyers.

Wholesale distributors, retailers and final consumers need assurance that a product identified as organic meets all required standards. For wholesale distributors, grower certification documents and/or affidavits may be required before the produce is purchased. Many retailer verification programs also rely on certification procedures. Some retailers randomly test produce in-house for pesticide residues. In-store advertising and promotion programs can increase retailer and consumer confidence and add value to the organic products. Such materials are available from the Texas Department of Agriculture once certification is achieved.

References

- Morgan, Jennifer and Bruce Barbour. 1989. “Marketing Organic Produce in New Jersey: Obstacles and Opportunities.”

- Fishman, Stuart. “Organic Produce and Farming.” United Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Association.

- Organic Market News and Information Service. “Organic Wholesale Market Report.” Various issues.

- Auburn, Jill S. 1986. “1985 Review of Organic Wholesale Market Report” Committee for Sustainable Agriculture, Colfax, California.

Appendix AEnterprise Budgeting Procedures

The topic of this section concerns the uses of budgeting in making production and marketing decisions. Every single day in the life of any business manager is filled with the monumental task of making decisions. Some of these decisions are general in nature. For example:

- Is the operation profitable enough to ensure survivability for the next 5 or 10 years or longer?

- Am I marketing a high quality product at a price that is competitive with industry prices?

- Does my business have a reputation for being honest, fair and considerate of the customer?

Other decisions tend to be more detailed in nature:

- Should new technology be implemented?

- Should additional land be purchased?

- What product mix will yield the highest profit?

The primary responsibility of any manager is to make decisions that will answer these types of questions and achieve the objectives of the firm. And, of course, maximizing profits is generally one of the most important objectives of any operation. But not only are managers faced with making decisions that affect revenues and costs of the firm, they also must implement solutions in a manner that is both efficient and effective.

Budgeting is a tool that may be used to help make these decisions. In general terms, budgeting may be defined as a plan to allocate resources among alternative uses. That includes money, labor, water and other resources that may be scarce or limited. Budgets also can be used to provide a basis for planning labor needs and for financing-deciding when to borrow and how much. They also provide a plan for when to buy supplies and when to sell the products. They are essentially a tool for managerial control and for evaluating performance and are especially effective when a record system designed for managing is already in place. Records are especially important in that they provide feedback for evaluating performance and provide information for developing and refining budgets. Thus, the effectiveness of budgeting is a function of how good your record keeping system is.

Though budgeting and record-keeping are valuable managerial tools, they require time to maintain and therefore represent a cost themselves. These costs of preparing and maintaining budgets and records must be included in the total cost of the business. But if they aid the manager in making sound management decisions, then the benefits certainly outweigh any costs involved. There are several types of budgets that may be of use to managers of any business. However, the focus of this discussion is enterprise budgets.

Enterprise Budgets

Enterprise budgets are those that generally account for all costs and all income associated with the production of one particular crop. They show when production activities will occur and how much of each input will be needed to produce a specified crop. Enterprise budgets are generally divided into three sections: (1) income section; (2) variable costs section; and (3) fixed costs section.

Estimating the income section of the enterprise budget is fairly straightforward. Simply multiply the number of units produced by the expected output price. Variable costs are those direct costs that increase as the level of production increases. They include costs of materials, as well as the cost of using machinery and equipment and labor. Consequently, these costs increase as more units are grown.

Variable costs are estimated by multiplying the quantities of each input used by their input prices. Their costs can be determined easily from invoices, but may have to be allocated to the appropriate enterprise. Materials should be charged directly to each enterprise according to the amount used. It is a little more difficult to allocate the costs of labor, machinery and equipment to any one enterprise. Detailed records really pay off in this regard. They greatly simplify this allocation process.

Once variable costs have been estimated, we must then turn our attention to fixed costs, which are probably the least understood. The most important fixed costs for any operation are those for land, buildings, machinery and equipment. The land charge is the opportunity cost of land and represents a return for its use in crop production (interest opportunity cost or a typical cash rent charge). Fixed costs for buildings, machinery and equipment include the “DIRTI 5.” That is, depreciation, interest, repairs, taxes and insurance.

When the income, variable cost and fixed cost sections of the enterprise budget have been completed, total costs of production for that enterprise are determined by summing variable costs and fixed costs, and the expected profits are simply the residual from income minus total costs.

Uses of Enterprise Budgets

Now that we’ve discussed how enterprise budgets are developed, let’s talk about how they can be used. First of all, the estimated profit can be compared with the estimated profits from other enterprises and used to select the more profitable crops and crop combinations.

Enterprise budgets also may be used to determine the maximum rental rate that can be paid for land. To do this, simply prepare the enterprise budget and omit any charge for land. The resulting expected profits would indicate the maximum rent that can be paid to just break even.

By the way, breaking even in enterprise budget terms is not necessarily a bad thing. Remember that all costs are being covered, including opportunity costs. Positive expected profits may be viewed as a return to risk or entrepreneurial talents.

Perhaps the most important use of enterprise budgets is that they help establish a minimum selling price based on production costs. Once the total costs of an enterprise are determined, then you know the base minimum price that should be charged to that product. The price you ultimately negotiate depends on what you feel is a fair return on your investment and the risks associated with producing the enterprise. By using costs of production as guide to pricing your products, you are at least guaranteeing that all your costs are covered and you are not producing products which are not profitable.

Appendix BMarket Window Analysis

The produce industry is characterized by unpredictable and volatile conditions. In light of this, potential growers must carefully evaluate marketing opportunities. Market window analysis is one tool that growers may use to help identify a time period (market window) during which crops may be marketed profitably. The market window technique is considered a simple, inexpensive and reliable screening device which may reduce some marketing risks and uncertainty. The data necessary for market window analysis includes the following:

- Estimates of prices received for the commodities. In the case of organic produce, OMNIS reports may be used or Market News Service reports for conventional produce may be used as a proxy. Preferably, weekly prices should be used.

- Estimates of production, transportation and marketing costs incurred. These may be developed by the grower using the enterprise budgeting format described in Appendix A or budgets developed by the Extension Service for conventional produce may be used as a proxy.

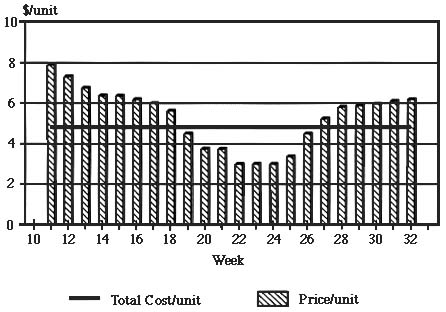

Once an estimated cost per unit for a specific organic crop has been determined, this figure can be compared to the average price that has been received historically for the commodity. An example of market window analysis for a hypothetical crop is shown graphically in Figure 3. In the example, weeks 11-18 at the beginning and weeks 27-33 at the end of the season are profitable for the grower. However, in weeks 19-26, the prices received do not cover total costs of producing, transporting and marketing the crop.

Figure 3. Example of market window analysis using a hypothetical commodity

As is readily seen, this technique enables the producer to determine whether the price for a particular time period win cover the cost of production. In weeks in which price is greater than the total cost of producing, transporting and marketing the crop, it is profitable for the producer. Thus, from a managerial standpoint, varieties and planting dates should be selected according to harvest dates that would be most profitable.