Lynn Brandenberger and Frank J. Daniello

Portuguese translation of this page provided by Artur Weber of homeyou.com

Economic losses due to weeds are encountered nearly everywhere weeds occur. To better appreciate the losses due to weeds, consider the following results of weed infestation:

Lower Yields, Less Efficient Use of Land

- Yields frequently are reduced by weeds competing with vegetables and other crops for water, nutrients, and light.

- Crop choice may be limited by the presence of high populations of weeds. Most vegetable crops will not compete effectively against heavy weed growth.

- Harvesting costs are commonly increased. Mechanical harvesting may be impossible.

- Root and crop damage may result from cultivation designed to control weeds. Soil structure may be destroyed by repeated cultivation, especially if the soil is wet.

Added Costs from Losses Due to Insects and Diseases

- Weeds may harbor insect and disease organisms that attack vegetables and other crops. For example: Carrot weevil and carrot rust fly may be harbored by the wild carrot, to later pose a problem for cultivated carrots. Aphids and cabbage root maggots may live in wild mustards to later attack cabbage, cauliflower, radish and turnips. Thrips thrive in ragweed and mustards, and may later attack vegetable crops. The virus diseases, squash leaf curl on watermelon and spotted wilt of tomatoes are carried by insect vectors that live on weeds in fields and along field borders.

Poor Quality Products

- All types of vegetables and other crop products may be reduced in quality, rendering them less marketable. Weeds can cause vegetables to be spindly, poorly developed and colored “leafy crops;” root crops can become poorly formed; fruits (tomatoes, peppers, beans) undersized, low quality, and poorly shaped; and, foreign matter originating from weeds occurring in crop products are a few examples.

More Problems in Water Management

- Weeds are becoming increasingly important in irrigation and drainage systems. Weeds also pose a problem by reducing the efficiency of water delivery and drainage systems.

- Less Human Efficiency

- Weed control involves a large portion of the effort required of a vegetable farmer to produce a crop. Weeds interfere with harvest operations making them less efficient. This effort and expense directly influences the cost of crop production and thus, the cost of food at the retail level.

Managing Weeds

Weeds are managed in three different ways; avoidance, control, and eradication.

Avoidance

Prevention means stopping a given species from contaminating an area. Prevention is often the most practical means of controlling weeds. This is best accomplished by making sure that new weed seeds are not carried onto the farm in contaminated crop seeds, transplants, irrigation water, and feed or from soil on machinery. Preventing existing weeds on the farm from flowering and going to seed and preventing the spread of perennial weeds which reproduce vegetatively are excellent approaches to avoiding weed problems.

Control

Control is the process of limiting weed infestations. The number of weeds is limited, so that there is a minimum of weed competition. Thus, the amount of control usually is balanced between the costs involved in control and the amount of possible negative effect on the crop. Control is the method usually used by producers toward annual weeds competing with vegetable crops.

Eradication

Eradication is complete elimination of all living weed plants, plant parts and seeds from an area. The two problems involved with eradication are eliminating the living plants, and, exterminating the weed seeds in the soil. Usually, it is far easier to eradicate the living plants than the seeds in the soil. However, for true eradication of weeds, both must be exterminated. This is very difficult and not economical.

Classification of Weeds

The methods needed for effective control or eradication of weeds are largely determined by the weed’s length of life, the time of year that it grows and its method(s) of reproduction. The three principal groups of weeds are annuals, biennials, and perennials.

Annuals

An annual plant completes its life cycle from seed in less than one year. Normally, they are considered relatively easy to control. This is true for any crop of weeds. However, due to their large number, abundance of seed and fast growth, annuals are very persistent. They often cost more to control than perennial weeds.

Most common weeds found in vegetable fields are annuals. There are two types: (1) summer annuals and (2) winter annuals.

Summer Annuals

Summer annuals germinate in the spring, make most of their growth during the summer, usually flower and produce seed and die in the fall. Their seeds lie dormant in the soil until the next spring. Summer annuals include such weeds as cocklebur, morningglory, pigweed, lambsquarters, common ragweed, crabgrass, foxtail and goosegrass. These weeds are most troublesome in summer crops like corn, peppers, tomatoes, okra, vine crops and most other spring and early summer planted vegetable crops.

Winter Annuals

Winter annuals germinate in late summer, fall and winter and usually flower and mature their seed in the spring or early summer before dying. Their seeds often lie dormant in the soil during the summer months. High soil temperatures (>125 F) tend to inhibit the germination of winter annual weeds. This group of annual weeds includes downy brome, cheatgrass, shepherdspurse, sowthistle, London rocket, wild mustard and henbit. These are troublesome mostly in winter and early spring growing crops such as carrots, onions, cole crops, lettuce, etc.

Biennials

A biennial plant lives for more than 1 year but not over 2 years. Only a few troublesome weeds fall in this group, and wild carrot, bull thistle, common mullein and burdock are examples.

There is usually some confusion between the biennials and winter annual group since the winter annual group normally lives during 2 calendar years and during at least 2 seasons.

Perennials

Perennials live for more than 2 years and may live almost indefinitely. Most reproduce by seed, and many are able to spread vegetatively. They are classified according to their method of reproduction as simple or creeping.

Simple Perennials

Simple perennials spread only by seed. They have no normal means of spreading vegetatively. However, if injured or cut, the cut pieces may produce new plants. For example, a dandelion or dock root cut in half may produce two plants. The roots usually are fleshy and may grow very large. Other examples include buckhorn plantain, broadleaf plantain and pokeweed.

Creeping Perennials

Creeping perennials reproduce by creeping roots (creeping above ground stems, stolen, or creeping below ground stems, rhizomes) in addition to seeds. Some examples include red sorrel, perennial sow thistle, field bindweed, wild strawberry, mouseear chickweed, ground ivy, bermudagrass, Johnsongrass, quackgrass, and Canada thistle. Also, some weeds maintain themselves and propagate by means of tubers which are modified rhizomes adapted for food storage. Jerusalem artichoke and nutsedge (nutgrass) are examples of weeds propagated by tubers.

Once a field is infested, creeping perennials are probably the most difficult group to control. Cultivators and plows often drag pieces about the field. To gain control, you often need continuous and repeated cultivation, repeated mowing for 1 to 2 years, soil sterilant chemicals or persistent and repeated use of other effective herbicides.

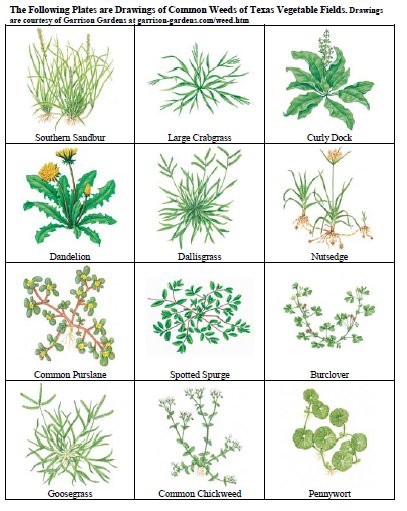

Weed Identification

One of the most important aspects of successfully managing or controlling weeds in crop fields is being able to properly identify the weeds. To aid in identification, drawings of common weeds that occur in Texas vegetable fields are presented at the end of this chapter.

Methods of Weed Control

Mechanical

Burial: This is effective on most small annual weeds. If all growing points are buried, most annual weeds are killed. Burial is only partly effective on weeds with underground stems and roots that are capable of sprouting; examples are field bindweed, Canada thistle, quackgrass, bermudagrass, johnsongrass, and nutsedge. For control, such perennials must be repeatedly cut off or buried until the underground parts are killed by carbohydrate depletion. After cultivation to control these perennials, it is important to clean your machinery to avoid infesting other fields.

Disturbance of the rooting system: Shallow cultivation with equipment such as sweeps, knives, harrows, finger weeders and rotary hoes are used for this purpose. The objective of this type of tillage is to loosen or cut the root system frequently, so the plant dies from desiccation (drying out) before it can reestablish its roots. Small weeds are most easily controlled by this method, and it is most effective in hot, dry weather with dry soils. In moist soils, or if it rains soon after tillage, the weeds may root and quickly reestablish themselves. In effect you transplant the weed, with little or no injury to it.

Most serious perennial weeds are easily destroyed by tillage when they are seedlings. These weeds, however, are difficult to kill after they develop rhizomes, stolons, tubers or reproductive roots.

Crop Competition

Crop competition is one of the cheapest and most useful methods a vegetable producer can use to control weeds. Often, it means using the best crop production methods, methods so favorable to the crop that weeds are crowded out. Competition makes full use of one of the oldest laws of nature, survival of the fittest. Some of the more competitive crops are closely planted bush green bean, cucumber, winter squash and sweet potato. Sweet corn, pole bean, watermelon and transplanted tomato, pepper and cabbage are intermediate. Slow or short growing crops such ascarrot, onion, okra, and direct seeded tomato, pepper, and cabbage are considered noncompetitive.

Carried one step further, a certain “balance of nature” is implied. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Every living organism in nature carries on the most ruthless kind of competition. “Nature’s balance” changes day by day. It is truly a survival of the fittest.

Weeds are naturally strong competitors. If not, they would fail nature’s test of “survival of the fittest.” Those weeds that can best compete always tend to dominate. For example, some weeds germinate and grow very quickly and may dominate a field seeded with a slower growing vegetable.

Weeds compete with crop plants for light, soil moisture and nutrients, carbon dioxide, and physical space. One wild mustard plant may consume twice as much nitrogen and phosphorus, four times as much potassium and four times as much water as a well developed onion plant. The average common ragweed consumes almost three times as much water as does a sweet corn plant. Weeds, as a group, have much the same requirements for growth as vegetables. For every pound of weed growth, the soil produces about one pound less of crops. The competition for nutrients can be easily seen from chemical analysis of weeds growing and competing with corn.

Early weed competition usually reduces crop yields far more than late season weedy growth. Therefore, early weed control is extremely important. Although late weedy growth may not seriously reduce yields, it makes harvest difficult, reduces crop quality, reinfests the land with seeds and may harbor numerous insects and diseases.

In planning a control program it is important to know the weed’s life cycle. Possibly the cycle can be interrupted to gain easy and effective control. In crop production, this may be a well timed chemical spray or a shift in planting date which enables the vegetable crop gets the upper hand or competitive advantage.

Mulching with plastic film or organic matter such as straw, hay, or any other similar material is largely a matter of competition for light. Most weed seedlings cannot penetrate the thick covering and are killed for lack of light. When using hay, realize that new weeds may be introduced.

Crop Rotation

Certain weeds are more common in some crops than in others. This is often due to time of year that the crop is grown. For example, pigweed, lambsquarters, common ragweed and crabgrass often are found in tomatoes, peppers, vine crops, sweet corn and in other summer cultivated crops. Wild mustard, volunteer small grains, wild garlic, cornflower and thistles are weeds that occur frequently in the fall and winter vegetables.

Rotation of vegetable crops can be an efficient way to reduce weed populations. A good rotation for weed control usually includes strong competitive crops grown in each part of the rotation.

Biological Predators and Diseases

In biological weed control, a “natural enemy” of the plant is used which is harmless to desired plants. Insects or disease organisms usually are the natural enemies. Parasitic plants, selective grazing by livestock and rodents, and highly competitive replacement plants are other forms of biological control. Examples of biological weed control exist in the literature. However, at the present time, there are no prime examples of biological control of weeds in vegetables fields, but research in this area is in progress.

Chemical Control

The use of chemicals for weed control in vegetables and other crops has developed rapidly since 1944. Chemicals used to control weeds are called herbicides.

Using Herbicides for Weed Control

There are three types of herbicides, depending upon their effects on plants: contact, growth regulators and soil sterilants.

- Contact herbicide cause rapid drying of planting tissue. Herbicides such as paraquat (Gramoxone) are nonselective contact herbicides.

- Growth regulating herbicides control physiological processes of plants such as cell division or expansion. Some also inhibit the plant ability to convert light into food energy. Examples are 2,4-D (sold under various trade names.)

- Soil sterilants are nonselective or selective herbicides used at high rates and are applied for the elimination of all plant growth. There are two categories of soil sterilants, persistent and nonpersistent. The persistent sterilants are normally used on noncropland areas such as railroads, highway barriers, etc. and around buildings. Nonpersistent sterilants such as Vapam and methyl bromide dissipate readily from the soil and are used in vegetable production prior to the growing season.

Time of Chemical Treatment

The time of chemical application may determine an herbicide’s usefulness in various crops. The time of application may be given with respect to the crop or with respect to the weed.

Preplant is any treatment made before the crop is planted. For example, trifluralin (Treflan) needs to be incorporated into the soil to kill weed seeds before planting the vegetable crop. Failure to incorporate a preplant incorporated herbicide can result in its loss as a gas, or can cause a herbicide to be broken down by the sun.

Preemergence is any treatment made prior to emergence of a specified crop or weed. The treatment can be applied preemergence to both the crop and weeds or to the weeds. Therefore, a statement as to preemergence to the crop, preemergence to the weeds, or preemergence to both the crop and the weeds will clearly establish the timing of the treatment.

Postemergence is any treatment made after emergence of a specified crop or weed. For example, metribuzin (Sencor) gives effective postemergence control for a number of broadleafed weeds and grasses, and can be used after tomatoes and potatoes are established.

Often the chemical may be applied postemergence to the crop, but preemergence to the weeds. For example, sweet corn may be cultivated when it is 24 to 30 inches tall, leaving the field free of weeds. Herbicides such as Dual or Lasso sprayed on the soil surface between the rows at this time may inhibit weed seed germination. This is often referred to as a layby treatment. The treatment is postemergence to the corn and preemergence to the weeds.

A listing of recommended herbicides cleared for use on vegetables is can be found in the Texas AgriLife Extension Service Bulletin B-5022 ‘Weed Control in Vegetables, Fruit and Nut Crops.’ This publication is available through Agricultural Communications, Texas A&M University.

Area of Application

Chemicals may be applied as a broadcast spray, as a band, as a directed spray, and as a spot treatment. Broadcast treatment, or blanket application, is a uniform application to an entire area. Band application usually means treating a narrow strip directly over or in the crop row. The space between the rows usually is not chemically treated, but is cultivated for weed control.

Band application reduces per acre chemical cost. The treated band is often 1/3 of the total area, with comparable savings in chemical cost. In addition, where the chemical has a long period of residual activity (remains active in the soil for an extended period of time), the smaller total quantity of the chemical reduces the residual danger to the succeeding crop. Directed sprays are applied to a particular part of the plant, usually to the lower part of the plant stem or trunk. Such sprays usually are directed at or just above the ground line.

Drop nozzles to spray between row crops give a directed spray treatment. The height of the nozzles is influenced largely by the size of the crop, the size of the weeds to be controlled and the spray angle of the nozzle. Spot treatment is the treatment of a restricted area, usually to control an infestation of a weed species requiring special treatment. Soil sterilant treatments often are used on small areas of serious perennial weeds to prevent their spread.

Applying Weed Control Chemicals

Refer to Chapter IX, Pesticide Safety and Application for equipment needs and calibration techniques.

In order to maintain spray efficiency and safe herbicide application, special attention should be given to cleaning equipment after each use. It is recommended that one sprayer be dedicated for herbicide application only. However, if only one sprayer is used for all pesticide application, it is imperative that the following steps be employed in the cleaning process.

- Rinse all parts of sprayer with water before and after any spray or cleaning operation is undertaken.

- If in doubt about the effectiveness of water alone to clean tank, pump, boom, hoses, and nozzles of the herbicide, use a cleaner.

- If hot water is used, let the solution stand in the tank for 18 hours. If cold water is used, leave it for 36 hours. Pump solution through the sprayer.

- Rinse tank and parts several times with clear water.

- If copper has been used in the sprayer before a weed control operation is to be performed, put 1 gal of vinegar in 100 gal of water and let the solution stay in the sprayer for 2 hours. Drain the solution and rinse thoroughly. Copper will interfere with the effectiveness of some herbicides.

Spray Adjuvants

An adjuvant is a substance added to a tank mix that increases the effectiveness of an herbicide, but generally doesn’t contain any herbicidal action itself. There are over 200 adjuvants on the market today, but most fall into a few general classes of action. Most herbicide labels will indicate if an adjuvant is needed.

The waxy surface of leaves causes water to bead up. The same way as water beads up on a freshly waxed car. Penetrants, surfactants, spreaders and wetting agents are soap-like adjuvants that break up water beads (and herbicide solutions), resulting in more thorough spray coverage. This is important in postemergence weed control with foliar applied herbicides. Sticking agents are designed to hold herbicide materials to the leaf surface. These often are combined with a spreader and are called spreader/stickers. When purchasing an adjuvant and when determining how much to add in a tank mix, it is important to consider the percent active ingredients.

Herbicide Bioassays

When crops are rotated, the herbicide used in the previous crop should be considered. While an herbicide may be safe to apply in one crop, it is possible that some herbicide residue may remain to damage another crop. The potential for a herbicide residue to cause damage to a succeeding crop is affected by the persistence of the chemical and environmental conditions that prevailed during the previous cropping season. There are analytical laboratories that can determine the concentration of herbicides in soil, but this doesn’t indicate the potential for crop injury.

Bioassays (observations of plant responses to the presence of a chemical) can be performed to determine the potential for crop injury. First, collect soil from an area that has not been treated with an herbicide for two years such as along a fence row, a ditch bank, next to your house, or barn, etc. In addition, collect soil from the area you suspect of having an herbicide residue. Collect a quart of soil from at least five spots, from both the herbicide-free and residue-suspect areas. Place the two soil samples in separate plastic bags and mix the soil up within each bag. Fill three Styrofoam cups with herbicide-free soil and three with residue-suspect soil. Label all the cups and plant five seeds of the crop you intend on growing in each cup. Water and grow the plants as normal. Once a week for a month, note any differences you see such as stunting, leaf curling, white or brown leaf margins, etc. If these injury symptoms are present in most of the samples from the suspect field and are absent in the herbicide-free samples, this is a good indication that an herbicide residue or some condition exists in the field that would be detrimental to that crop. The safest way to prevent crop damage from herbicide residues is to follow the labeled recommendations concerning rotational crops.

Six Easy Methods of Reducing Costs and Improving Weed Control

- Always read and follow the directions on the label.

- Calibrate your spray rig and keep it in good working order.

- Apply herbicides as a band rather than broadcast.

- Apply postemergence sprays when weeds are small.

- Make a map of the major weed species in the field and use it the following season to develop your spray program.

- Plant competitive crops in weedy areas and noncompetitive crops in cleaner areas of the field.

See also: Quick Guide for Herbicides Used in Texas-Grown Vegetable Crops by Russell W. Wallace, Extension Vegetable Specialist Texas AgriLife Research & Extension Center, Lubbock, TX