By Michael Cook (June 2017)

Vineyard floor management (VFM) is an often overlooked practice that can substantially influence the performance of a vineyard. The major components involved in VFM include controlling weed pressure, conserving soil, and managing soil water.

Weeds compete with vines for nutrients and water in the soil, can harbor pests and disease, and in a young vineyard can cause shading issues and inhibit good spray coverage. Weed control is particularly important during the first few years of vineyard establishment but should generally be carried out for the life of the vineyard. Before planting a vineyard, invasive and perennial weeds should be suppressed to minimize pressure once the vineyard is planted. As previously mentioned, young vines are especially sensitive to weed pressure, this is because they are unestablished and have a minimal root system, thus mining for nutrients and water is limited to a small area in the soil profile. In order to prevent weeds from competing with vines for nutrients and water, growers should maintain a three to four foot weed free strip under the trellis.

Row middle management is another component to weed management. To minimize erosion, alleviate soil compaction, and prevent rut formation in the vineyard row middles, most growing regions in Texas contain some sort of cover crop. For most growers, this simply consists of native grass. Intentional seeding of an annual or perennial cover crop is also common. Annuals are often seeded in the row middle in Fall and can include mustard and cereal crops, annual ryegrass, and nitrogen fixing legumes such as clover and vetch. They are often tilled under mid to late Spring. The seeding of perennial cover crops offers the benefit of providing soil cover over multiple seasons without the need to replant but must be managed more closely. Native mixes of grasses and wildflowers are recommended. Ensuring the row middles are properly maintained will help prevent unwanted weed infestations under the trellis and reduce insect habitat.

Weeds found in the vineyard can be categorized into two taxonomic groups; the dicots (broadleaves) and monocots (i.e. grasses and sedges). There are many differences between the two groups, including how a grower may manage them. This is one reason why proper weed identification is critical as not all weeds are controlled in the same manner.

Weeds can be further defined by their life cycle. Annuals grow and seed out during one season and either germinate in the Spring or Fall. Biennials grow vegetatively for one year and then set seed the following year; thistle is an example of a biennial. Perennials on the other hand are long lived and therefore are often the most challenging weed to control in the vineyard. Not only do perennial weeds reproduce via seed, they can also propagate vegetatively via rhizomes, stolons, bulbs or tubers.

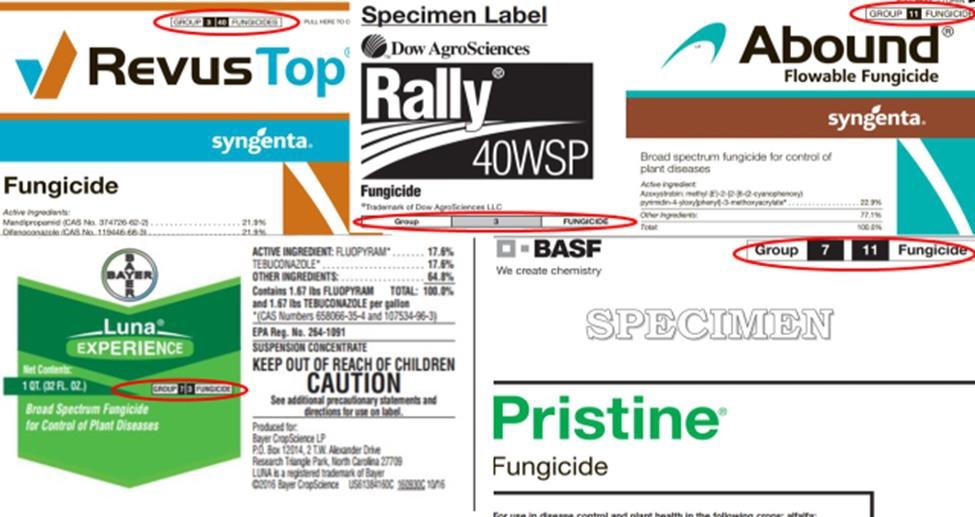

Both cultural and chemical methods of weed management are utilized in the vineyard, often in tandem. Cultural controls include hand weeding, mulching, burning via propane tank, or with a mechanical implement attached to a tractor. Avoiding trunk and root zones when applying cultural control methods is necessary to prevent diseases such as crown gall as well as serious mechanical injury to the vine. Chemical control is popular with many growers because it can be effective, often requires less labor and equipment, applications can be made quickly, and is cost effective. For optimum efficacy, the appropriate herbicide must be safely applied at the right time. Herbicides are categorized into both pre- and post-emergent types. A pre-emergence herbicide works by preventing weed seeds from germinating and is typically used to control annual weeds. Timing is of the utmost importance. Additionally, many products require a rain event for the product to work effectively. There are a handful of pre-emergence herbicides that target specific weeds and are labeled for use in the vineyard. Read the labels carefully as there are often vine age and soil type restrictions. Post-emergence herbicides are applied once weeds are visually present and are either selective or non-selective in nature. Selective herbicides only control very specific weed species and pose little risk to grapevines. Non-selective herbicides, such as glyphosate, will cause damage to any green tissue it encounters, regardless of species. Glyphosate is routinely used in the vineyard to manage weeds, however, since it is non-selective, grapes are sensitive to spray drift. Installation of grow tubes during the season is recommended to protect young vines from accidental spray drift. Spraying under appropriate weather conditions, using a cone style protector on the spray wand, and installing large droplet size nozzles are additional measures that will help reduce the chance of spray drift. Furthermore, post-emergence herbicides are either labeled as contact or systemic. Contact herbicides damage the plant tissue that receives the herbicide and has a fairly rapid effect on weeds. Systemic herbicides are slower acting products but can translocate throughout the plant, including the roots, which helps ensure a permanent kill. Contact herbicides are often used against annual weeds while systemic herbicides work well for controlling difficult perennial species. It should be noted that “tank mixing” a contact and systemic herbicide or applying one shortly after another is not recommended. Applying these two in tandem with the mindset of ensuring high weed suppression rates is erroneous and is a waste of resources. Using the correct product for weed species present in the vineyard at the proper time is a skill every grower should develop. Controlling weeds is not just for aesthetic purposes but can significantly improve vine performance and should be a part of every growers strategic plan.

For assistance in cover cropping, weed identification, product selection, how to calibrate your sprayer, and what kind of equipment may be suitable for your vineyard operation please contact your local Extension Viticulture Specialist. When purchasing herbicide always read the label and be familiar with the active ingredient(s).

Under no circumstances should growers ever apply phenoxy type herbicides, such as 2,4-D or dicamba, in or near a vineyard. Spray drift and vapor drift from these chemicals can have a detrimental effect on the vineyard, even with just a single application. Phenoxy herbicides are common ingredients in many products used to control broadleaf weeds in residential and commercial lawns and landscapes, land under highway jurisdiction, pastures, and farming operations. The Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service recently published an in-depth article discussing the danger that phenoxy herbicides pose to grapevines. Please contact your local viticulture specialist for a pdf copy or download your copy here.