By Justin Scheiner (June 2017)

One of the most challenging aspects of vineyard management is controlling vine vigor. Depending on your situation, this could mean trying to increase vigor to develop a full canopy that’s capable of ripening a sizeable crop, or reduce vigor to prevent shoots from overgrowing the trellis. In Texas, that can even change from one year to another due to our erratic weather. Two examples that quickly come to mind are 2011, a historic drought year, and 2015, the wettest year on record for the state. Both years presented very different challenges for vineyards, and therefore different responses were needed to manage vine growth. In this article we will review factors that influence vine vigor and highlight possible points of control.

Vigor is frequently defined as the relative growth rate of a grapevine or a shoot. Vigorously growing shoots are characterized by having long internodes (the smooth portion of a shoot between nodes), large leaves, and they often have actively growing lateral shoots. Grapevines are indeterminate, so they will continue to grow indefinitely as long as conditions are favorable.

Genetics play an important role in vine vigor as some cultivars such as Cabernet-Sauvignon and Blanc Du Bois are inherently more vigorous than others. Likewise, rootstocks have the potential to influence vine vigor. Rootstocks with V. riparia x V. rupestris parentage such as 101-14Mgt and 3309C are generally less vigorous than those with V. berlandieri x V. rupestris parentage such as 1103P and 110R. When establishing a vineyard, it’s important to select a rootstock that is adapted to the soil conditions of the site, but one must also consider its vigor potential. For example, 140Ru, a V. berlandieri x V. rupestris rootstock, has many desirable characteristics such as high drought resistance and salt tolerance, but it is known to be extremely vigorous and therefore not frequently used. However, it could be appropriate on a site with very low vigor potential due to restrictive soil properties.

The role that soils play in vine vigor relates to water and nutrient holding capacity. Soils that have a significant clay content or a fine texture (or high organic matter which is rare in Texas) have a higher water and nutrient holding capacity than coarse or sandy soils. Similarly, soil depth has an important influence. In an ideal situation, a grape grower would carefully control water availability all season with irrigation, but that’s not typically the case in Texas due to spring and summer rains that can occur in excess. Regardless, one should carefully determine when and how much irrigation water to apply based soil properties, weather, and other observations or data collected. It’s easy to assume that overwatering is more common than under-watering, but that’s not always the case. As the old saying goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure, and this applies quite well to irrigation. It is typically necessary to customize the irrigation strategy for each individual block to account for differences in soil, vine age, cultivar, etc.

Vineyard floor management also impacts vigor through the availability and competition for water and soil nutrients. The least competitive floor management system is a killed ground cover or mulch, followed by bare soil, and a living ground cover. Mulches and killed ground covers reduce evaporation of water from the soil surface thereby increasing water availability. In contrast, living ground covers compete with vines for these resources which is principally why weed control in a new vineyard is so important, particularly under-vine.

The most common under-vine treatment in vineyards with a ground cover is a weed-free strip between 2’ and 5’ wide. The wider the weed-free strip is, the less competition, and vice versa. Although it is possible to allow vegetation to grow directly beneath vines to maximize competition, difficulties in managing this vegetation generally deter most growers. If choosing a cover crop to plant, one should consider the competitive nature of the species in addition to other attributes.

It’s tempting to think that planting vines close together will moderate vigor by increasing root competition, but research has proven that this does not work under vigorous soil conditions. Rather, this may exacerbate the problem by reducing the trellis space provided for each vine. For soils with a low water and nutrient holding capacity, the addition of organic matter through cover cropping or a direct application can provide significant benefits.

Any essential plant nutrient has the potential to limit vine vigor when deficient, but many growers think of nitrogen because grapevine vigor can be affected by nitrogen application levels. In most soils, nitrogen needs to be applied annually to maintain a strong, healthy canopy, but it’s important to consider all sources of available nitrogen such as organic matter, and soil type when determining how much and how often to make an application. Soils with a poor nutrient holding capacity (sandy soils) will need more frequent applications than heavier soils. If canopy development is poor, it may be a good idea to reexamine your fertility program to determine if this is a limiting factor.

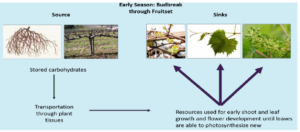

One final aspect of vigor to consider is shoot number and crop. At some point you have likely heard that dormant pruning is an invigorating action, or that shoot number is inversely proportional to shoot vigor. This is in reference to the fact that early season shoot growth is fueled by energy that was stored in the vine in the previous season. Developing shoots share the same fixed pool of energy so the more shoots there are the less vigorous they will be. During dormant pruning, we aim to match the number of buds retained or future shoots to vine size in an attempt to balance shoot growth with the crop. However, there may be times where retaining additional shoots is desirable, but will result in overcrowding and excessive shading. This is why divided canopy systems were created. They facilitate higher shoot numbers to combat vigor, but these systems require more intensive management and may not be compatible with mechanization.

Around bloom, the carbohydrate stores from the previous season are typically depleted, and in situations where shoot vigor is inadequate, it may be necessary to reduce the crop through shoot or cluster thinning. The resulting compensatory growth is generally more significant when clusters are removed early. Waiting until later to remove fruit results in a loss of energy that could have gone to shoot development. This is why all fruit should be removed from first leaf vines, and why it’s necessary to closely monitor canopy development in young vineyards. When applied properly, cluster thinning can be an effective vigor management tool.

Finally, in those situations where vigor cannot be adequately controlled, canopy management can often provide the necessary relief.