Coming soon

Managing Vines After Hail Damage

by Pierre Helwi (June 2017)

If you ask a winegrower in Texas about his biggest fear, the answer depending on region may well be hailstorms during the season.

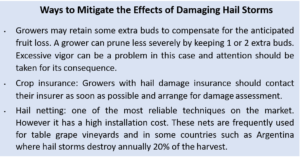

Damage from hail can range from random spots on leaf blades and scares on shoots to total defoliation, broken branches and complete crop loss. Usually, if damage occurs early in the season, vines have the ability to recover by reshooting from secondary buds and wounds can “heal” properly. However the degree of recovery depends on vine health and vigor, timing of the damage and its intensity.

In which situations should the vineyard be retrained after hail damage?

If damage happens early in the season and the potential number of healthy clusters is significant and economic (more than 60%), simply leave the inflorescences and wait for the canopy to regrow and reshoot. In this case, many new shoots on the vine will grow, producing a second crop which will most likely not ripen to an acceptable level by the time the initial crop has achieved target Brix levels. Consequence harvest decisions may be more difficult.

If damage is more than 60%, growers may consider knocking broken shoots to the basal buds and allowing new ones to develop from secondary buds. In fact, shoot loss will stimulate the initiation of fruitful buds from secondary and latent buds, with minimal effect on bud fruitfulness or crop in the following season. This practice would allow the development of healthy canes with a good quality wood for the next season.

Secondary bud fruitfulness is lower than primary buds and it is variety dependent. Varieties such as Cabernet-Sauvignon and Syrah have relatively fruitful secondary buds compared to Riesling or Chardonnay. Clusters on secondary shoots will ripe later in the growing season.

In a later season hail damage scenario (after flowering), retraining vines is not recommended. Shoot loss may stimulate some new canopy growth from dormant buds, however fruit ripeness will be greatly delayed, and the quality is likely to be affected.

In young vines, the scarring on a shoot that will eventually become the trunk can interfere with sap flow and may provide sites for entry of trunk diseases. In this case, cutting back wounded shoots and retraining a new shoot as a trunk should be considered.

Vines (A) three days and (B) one month after hailstorm. Secondary shoots emerged from secondary and latent buds after an intense hailstorm early in the season (April 16, 2017).

What about the pest management program?

In wet and warm season, scarred berries will be prone to bunch rots and Botrytis cinerea, and sour rot organisms in addition to different insects and pests. An adequate fungal disease program will protect sound berries from infection but cannot prevent the development of rot on damaged berries (attention required to the pre-harvest interval for all fungicides). An opened canopy allowing the circulation of air at the fruit zone will also help to maintain a lower disease pressure.

After hail storm, the application of a broad-spectrum fungicide may help avoid opportunistic fungi, including Botrytis cinerea. A botrytis-specific fungicide may be helpful as well. Elevate, Vangard, Scala or the highest label rate of Pristine would be suitable choices. The development of Crown gall and wood diseases such as Eutypa dieback and Botryosphaeria can also be an issue for wounded shoots and canes.

Summary

After a hailstorm, it is important to inspect damage to plants as soon as possible. If damage is extensive and early in the season (between budbreak and bloom), re-training of vine parts may be necessary and pruning may need to be adjusted to obtain healthy wood and sufficient buds for next season. If the damage occurred pre-veraison, the injured berries may scar over and continue developing, or they may shrivel without rotting. Crop thinning might be appropriate for a homogenous ripening pattern and for young and weak vines.

Managing Yield In The Spring Begins During Harvest

By Jacy Lewis (June 2017)

Decisions made in the spring can dramatically impact the crop you harvest months down the road. The ability to accurately estimate the potential yield of a block enables you to determine how much fruit you will likely have at harvest and plan accordingly. Most importantly, it can help you assess the ability of your vines to ripen the crop they are set to produce. This is the only opportunity to reduce crop load in a way that will change the quality of the fruit you harvest and potentially reduce the stress that a large crop can place on young or weak vines. The decision to reduce yield by crop thinning can be a complex one, taking into account a variety of factors.

How to make the decision to thin is beyond the scope of this article. Here we will detail the basics of how to estimate yield, the first component of how you will manage your crop yield for the rest of the season. Additional more time-consuming techniques can be used to get higher precision in your estimates that are also beyond the scope of this article.

Estimating next year’s crop starts at harvest this year. Estimating yield in a given season requires that you have available historical records of cluster weights at harvest. Because cluster weights vary year to year, it is important that you collect data yearly in order to eventually obtain a reliable average that you can work with in subsequent years. You will find that this is likely the single largest variable in your equation, so good record keeping here is essential. In young blocks, you may rely on averages from other blocks of the same variety that you have collected data on in the past, but there is no substitute for collecting data from each variety and block to get the best prediction of average expected cluster weight.

When collecting average cluster weights, it is tempting to pull clusters from a harvest bin for weighing. There are a number of problems with this practice. First, it is too easy to introduce sampling bias when one is forced to look at a bin and choose clusters. There is the tendency to choose either large or small clusters inadvertently. Additionally, at this point clusters may have become damaged and/or have lost berries. A better method is to randomly select vines from your vineyard map then hand harvest these individual vines. One caveat here is that it is best to avoid using vines on the edge of your vineyard as they are commonly not representative of the vineyard as a whole. So choose from vines not at the end of a row or from the outside rows of the block. Count the total number of clusters per vine. Weigh all of the clusters together, then divide that number by the total number of clusters. This will give you the average cluster weight for that vine. You can then average the (mean cluster weight) for all of the sampled vines. This will give you the average cluster weight for that vineyard block.

How many vines need to be sampled depends on the number and uniformity of vines in the block. In a block with little variability, a sample size representing 1%-2% of the total number of vines may be sufficient. In an established block that has a mix of non-bearing and bearing vines, or vines of multiple ages and skips, it is necessary to increase this number. Any increase in the number of vines sampled will increase the accuracy of your predictions.

When spring yield prediction is done, you must determine the number of bearing vines per block as well as the average number of clusters per vine. Be sure to make adjustments to your estimates by assessing the vineyard for vines that may have been lost in the previous year, and tracking the number of replants, or retrained vines that will not be expected to bear in the current growing season. It is important that this count be done accurately, as even a small over or under estimate of the number of bearing vines can result in a large decrease in the accuracy of yield. The smaller the block, the greater the importance of the accuracy of this number.

Estimating clusters per vine is done in a similar fashion to estimating cluster weight at harvest. A minimum of 1%-2% of the vines in the block, provided it is uniform, should be selected randomly and the number of clusters on each vine carefully counted. You must be sure you wait until developing clusters are all exposed. Waiting until berry set will help ensure better accuracy if set is low.

Finally, the equation for estimating crop yield is as follows:

Yield in tons/block= 1 / 2,000lbs X Vines/block X Clusters/vine X Average historical cluster weight

Managing Vine Vigor

By Justin Scheiner (June 2017)

One of the most challenging aspects of vineyard management is controlling vine vigor. Depending on your situation, this could mean trying to increase vigor to develop a full canopy that’s capable of ripening a sizeable crop, or reduce vigor to prevent shoots from overgrowing the trellis. In Texas, that can even change from one year to another due to our erratic weather. Two examples that quickly come to mind are 2011, a historic drought year, and 2015, the wettest year on record for the state. Both years presented very different challenges for vineyards, and therefore different responses were needed to manage vine growth. In this article we will review factors that influence vine vigor and highlight possible points of control.

Vigor is frequently defined as the relative growth rate of a grapevine or a shoot. Vigorously growing shoots are characterized by having long internodes (the smooth portion of a shoot between nodes), large leaves, and they often have actively growing lateral shoots. Grapevines are indeterminate, so they will continue to grow indefinitely as long as conditions are favorable.

Genetics play an important role in vine vigor as some cultivars such as Cabernet-Sauvignon and Blanc Du Bois are inherently more vigorous than others. Likewise, rootstocks have the potential to influence vine vigor. Rootstocks with V. riparia x V. rupestris parentage such as 101-14Mgt and 3309C are generally less vigorous than those with V. berlandieri x V. rupestris parentage such as 1103P and 110R. When establishing a vineyard, it’s important to select a rootstock that is adapted to the soil conditions of the site, but one must also consider its vigor potential. For example, 140Ru, a V. berlandieri x V. rupestris rootstock, has many desirable characteristics such as high drought resistance and salt tolerance, but it is known to be extremely vigorous and therefore not frequently used. However, it could be appropriate on a site with very low vigor potential due to restrictive soil properties.

The role that soils play in vine vigor relates to water and nutrient holding capacity. Soils that have a significant clay content or a fine texture (or high organic matter which is rare in Texas) have a higher water and nutrient holding capacity than coarse or sandy soils. Similarly, soil depth has an important influence. In an ideal situation, a grape grower would carefully control water availability all season with irrigation, but that’s not typically the case in Texas due to spring and summer rains that can occur in excess. Regardless, one should carefully determine when and how much irrigation water to apply based soil properties, weather, and other observations or data collected. It’s easy to assume that overwatering is more common than under-watering, but that’s not always the case. As the old saying goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure, and this applies quite well to irrigation. It is typically necessary to customize the irrigation strategy for each individual block to account for differences in soil, vine age, cultivar, etc.

Vineyard floor management also impacts vigor through the availability and competition for water and soil nutrients. The least competitive floor management system is a killed ground cover or mulch, followed by bare soil, and a living ground cover. Mulches and killed ground covers reduce evaporation of water from the soil surface thereby increasing water availability. In contrast, living ground covers compete with vines for these resources which is principally why weed control in a new vineyard is so important, particularly under-vine.

The most common under-vine treatment in vineyards with a ground cover is a weed-free strip between 2’ and 5’ wide. The wider the weed-free strip is, the less competition, and vice versa. Although it is possible to allow vegetation to grow directly beneath vines to maximize competition, difficulties in managing this vegetation generally deter most growers. If choosing a cover crop to plant, one should consider the competitive nature of the species in addition to other attributes.

It’s tempting to think that planting vines close together will moderate vigor by increasing root competition, but research has proven that this does not work under vigorous soil conditions. Rather, this may exacerbate the problem by reducing the trellis space provided for each vine. For soils with a low water and nutrient holding capacity, the addition of organic matter through cover cropping or a direct application can provide significant benefits.

Any essential plant nutrient has the potential to limit vine vigor when deficient, but many growers think of nitrogen because grapevine vigor can be affected by nitrogen application levels. In most soils, nitrogen needs to be applied annually to maintain a strong, healthy canopy, but it’s important to consider all sources of available nitrogen such as organic matter, and soil type when determining how much and how often to make an application. Soils with a poor nutrient holding capacity (sandy soils) will need more frequent applications than heavier soils. If canopy development is poor, it may be a good idea to reexamine your fertility program to determine if this is a limiting factor.

One final aspect of vigor to consider is shoot number and crop. At some point you have likely heard that dormant pruning is an invigorating action, or that shoot number is inversely proportional to shoot vigor. This is in reference to the fact that early season shoot growth is fueled by energy that was stored in the vine in the previous season. Developing shoots share the same fixed pool of energy so the more shoots there are the less vigorous they will be. During dormant pruning, we aim to match the number of buds retained or future shoots to vine size in an attempt to balance shoot growth with the crop. However, there may be times where retaining additional shoots is desirable, but will result in overcrowding and excessive shading. This is why divided canopy systems were created. They facilitate higher shoot numbers to combat vigor, but these systems require more intensive management and may not be compatible with mechanization.

Around bloom, the carbohydrate stores from the previous season are typically depleted, and in situations where shoot vigor is inadequate, it may be necessary to reduce the crop through shoot or cluster thinning. The resulting compensatory growth is generally more significant when clusters are removed early. Waiting until later to remove fruit results in a loss of energy that could have gone to shoot development. This is why all fruit should be removed from first leaf vines, and why it’s necessary to closely monitor canopy development in young vineyards. When applied properly, cluster thinning can be an effective vigor management tool.

Finally, in those situations where vigor cannot be adequately controlled, canopy management can often provide the necessary relief.

Introduction to Vine Balance

By Brianna Hoge (February 2018)

Vine balance is defined as the state at which vegetative vigor and fruit load are in equilibrium and can be sustained indefinitely while maintaining healthy canopy growth, adequate fruit production, and high fruit quality. It is a critical concept in professional vineyard management. Balanced vines have increased light in the canopy, resulting in minimized leaf and fruit shading, thus maximizing carbohydrate production for vegetative growth and fruit quality. Optimizing light and temperature can improve color, enhance flavor compounds, decrease pH and potassium content, and reduce vegetative aromas. Balanced canopies also have increased airflow, which helps reduce canopy moisture and improves spray penetration, both of which are crucial to reducing disease risk. All these factors lead to healthy, productive vines capable of producing high quality fruit. Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all recommendation that can be implemented.

Environmental factors impacting balance revolve around characteristics such as soil depth and type and nutrient and water availability. Vineyards with deep fertile soils and relatively unlimited moisture and sunlight are at greater risk of growing excessively vigorous vines. This type of vine produces shoots with large leaves, long nodes, and excessive lateral shoot development. The abundance of vegetation means that the fruit and renewal zones are shaded, resulting in poor bud development for the following year’s crop, inferior fruit quality, higher disease pressure, and poor periderm formation, decreasing cold hardiness. These same vines, with proper management practices will be able to produce a balanced ratio of fruit to canopy allowing for quality fruit production as well as plentiful nutrient storage reserves to promote winter hardiness and sustain post-budbreak growth the following season.

On the contrary, vines planted in soils with limited water and nutrient resources will be able to produce less canopy and will have lower carbon levels. Therefore, they will not be able to sustain as large a crop load. Drought, shallow soils, weed competition, insufficient nutrients, and disease pressure can lead to insufficient vigor- sparse canopy with little or no ability to ripen a crop. Another route to the same problem can be found in overcropping. Excess crop load without enough canopy to support it can cause insufficient photosynthetic capacity, poor fruit maturation, and increased cold susceptibility. The short-term benefits of high yields must be weighed against the negative impact on fruit quality and the long-term effects this stressor may have on vineyard health and longevity.

Rootstock and scion (cultivar) also play a role in vine growth and development. Many rootstocks have beneficial qualities, such as increasing and decreasing vigor of various grape cultivars, which demonstrate a range of vigor on their own. Research has shown that rootstocks have the potential to affect not only growth potential, but fruiting potential, pest resistance, water efficiency, and nutrient uptake, all of which influence vine growth and development (Skinkis and Vance, 2013). This should be taken into account when selecting rootstocks in order to maintain proper vine balance.

Vineyard management practices which affect vine balance include irrigation, fertilization, pruning, thinning, and vineyard floor management. All of these practices, conducted strategically can either enhance or decrease vine balance. High vigor vines may benefit from competition with cover crops for nutrients and water keeping growth in check, while lower vigor vines may be unable to obtain adequate resources for healthy growth and fruit development. Similarly, fertile soils with good water holding capacity are likely to produce high vigor vines, and will not require the fertilization and irrigation inputs a site with low vigor vines and lower nutrient and water availability would. Management practices should be site specific and keep cultivar characteristics in mind in order to be effective in steering vines towards balance.

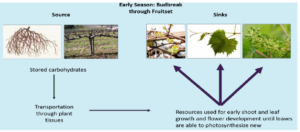

Balance of Source vs. Sinks

To understand vine balance, we need to understand grapevine physiology and the concept of carbon sources and sinks. During the growing season, carbon is produced through the photosynthetic activity of the canopy (source). Before vegetative growth is adequate to supply the rest of the vine, the carbon reserves stored the previous season function as a source to support early season shoot growth and flower development (sinks). The major carbon sources and sinks within a vine changes over the course of growing and dormant seasons as depicted below.

Remember: Imbalanced vines lead to lessened ability to transition into dormancy via shoot lignification and cold hardiness reduction. Overly vigorous vines continue to grow past véraison and have excess canopy shading and less shoot lignification late in the season. Research suggests that vine hardening is influenced less by crop load than canopy shading caused by excess vegetation, so canopy management in addition to crop load is critical to preventing frost damage (Howell and Shaulis, 1980; Reynolds et al., 1986).

Measuring Vine Balance

Pruning weight and yield reflects the final size of vines given environmental factors and management practices. It should be noted that if crop thinning is done at lag phase, data can be collected at the time of thinning to calculate potential total crop load and compare it to actual crop load at harvest (Skinkis and Vance, 2013). A Ravaz value of 5-10 is considered optimal for Vitis vinifera cultivars in warmer climates. Values at the low end of the range are considered under-cropped or highly vigorous, and there’s a larger canopy size compared to fruit yield. Conversely, values at the high end of the range are considered over-cropped or low vigor and have larger fruit yield compared to canopy size. In either case, vines are unbalanced, resulting in unsustainable vine growth and fruit quality.

Vine balance can be measured several ways, but the two most common are use of the Ravaz index and the leaf area to fruit yield ratio. The Ravaz index, also known as the crop load method, is the most common and practical for commercial growers. It’s calculated using fruit yields at harvest and dormant pruning weights during winter following harvest.

Ravaz value = vine yield / dormant pruning weight

Implementing Good Practices

Canopy management through direct and indirect methods. Direct methods include shoot thinning, leaf removal, and crop thinning; while indirect methods include irrigation, fertilization, and vineyard floor management.

Vineyard floor management, including weed control, and cover cropping can alter vine vigor by changing nutrient and water availability. High vigor vineyards benefit from the use of cover crops, as they reduce vine growth and restrict potential rooting volume. Research conducted in high vigor vineyards showed a reduction in vine vigor and natural yield, producing vines that were more balanced than those in tilled, non-grass cover treatments. For moderate or lower vigor vineyards, certain cover crops may enhance vigor by increasing soil moisture or nutrition. For instance, alternating legumes or grass cover and tillage in alleys can enhance soil nutrient and moisture levels, while providing a more moderate level of competition, for better vigor management.

Crop management through shoot thinning is performed after budbreak and before shoots are 6 inches long. It assists in optimizing fruit production and canopy density. Typically, 3-5 shoots per linear foot of row is recommended. Shoot thinning reduces competition among shoots for carbohydrate and nutrient reserves for growth and development before carbohydrate accumulation begins in spring. For weak vines, leaving fewer shoots can produce better growth. On a vigorous vine, removing too many shoots can lead to increased vegetative growth of remaining shoots and less than ideal yields. The reduction of fruit that occurs as a result of over-thinning in vigorous vines can lead to less than ideal yields and out of balance vines.

Leaf removal around the cluster zone is often conducted to allow for sunlight exposure and airflow. This practice should be done earlier in berry development, when flavonoid compounds are which act as a sort of sunscreen are produced. If conducted late in the season, fruit may become sunburned, as there are lower levels of these protective compounds at or around véraison. Increased airflow, as a result of leaf thinning provides the added benefit of reduced incidence and severity of diseases such as powdery mildew or Botrytis bunch rot. In healthy vines, leaf removal doesn’t greatly affect carbohydrate production when implemented early in the season (shortly after fruit set), and it can enhance the production of secondary metabolites that enhance wine quality.

Crop Level Management by fruit thinning adjusts yields to obtain a balance between canopy growth and crop load, while enhancing fruit quality. Vigorous vines with large canopies are usually capable of ripening more fruit than low vigor vines. Environmental and management practices must also be considered in determining the amount of crop to remove during thinning. For instance, in cooler climates, a greater leaf area to fruit ratio is needed to properly ripen a crop compared to warmer climates. For low vigor vines, light thinning may be sufficient, but if the vine is also unhealthy, heavy thinning is recommended to ensure adequate carbohydrates are being produced to ripen fruit and store for dormant season reserves. It is generally believed that removal of fruit increases canopy growth and fruit quality, but this may differ depending on circumstance (Vance et al., 2013).

When appropriate, thinning can enhance ripening. Timing of crop thinning is very important to maintaining vine balance. While dormant pruning reduces the potential number of clusters developed, cluster thinning may be also be required depending on the level of balance in a given vine. In lower vigor vines, late thinning (at véraison) may result in heavy competition between shoots and fruit for carbohydrates and push vines further out of balance. This type of vine should be thinned between inflorescence and fruit set. In higher vigor vines, waiting to thin until véraison may help keep canopy growth in check and reduce canopy management throughout the season.

If carbon sources are limited, inflorescences and flower number per inflorescence can be reduced, resulting in lower yield the following season. However, crop level alone may not compete for resources enough to reduce fertility. Research has shown that timing of thinning can impact effectiveness. Early thinning resulted in greater bud fertility, while thinning at véraison had no effect. This may be due to the fact that there is less competition for carbon resources early in the season, and latent buds initiate as early as pre-bloom (Howell, 1999; Vance, 2012).

While achieving Vine Balance can be a complex task, working toward this goal will offer both short term reward of maximizing both fruit quality and yield as well as the long term reward of a healthy and productive vineyard that is resistant to injury and disease.